A French ship that sank following an 1856 collision while on its maiden voyage has been found off the Massachusetts coast, according to a report.

For nearly 170 years, Le Lyonnais lay at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

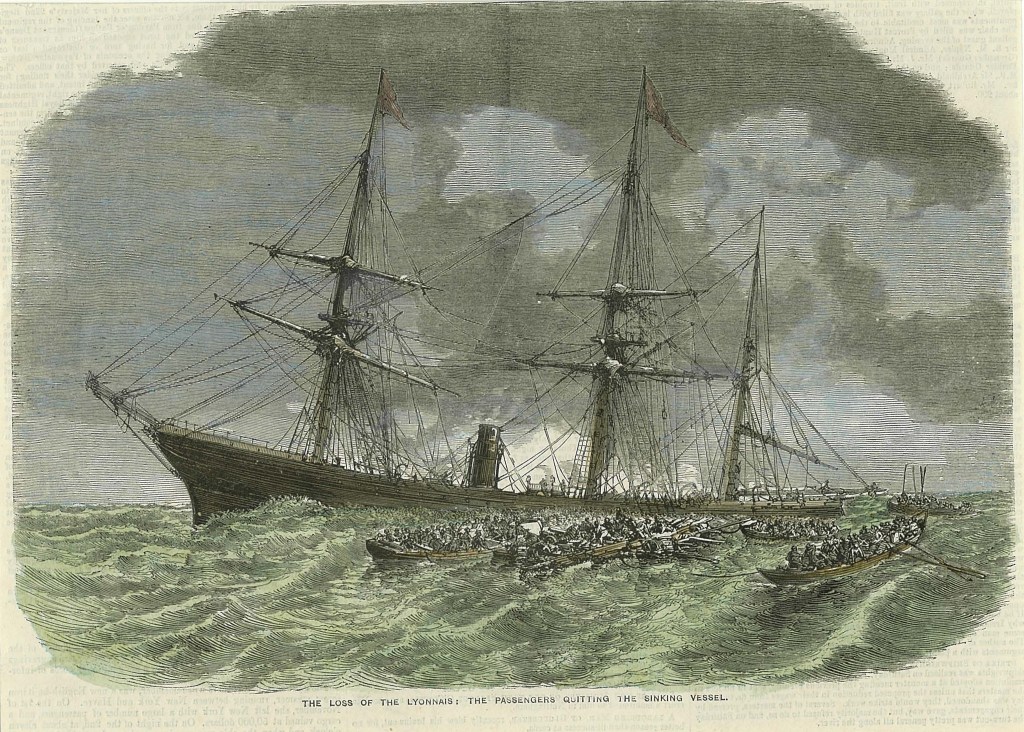

The fog-induced crash killed more than 100 passengers and crew members.

However, last month, a dive team — headed by two New Jersey residents — found its wreckage about 200 miles near the Massachusetts coast, The Boston Globe reported.

The state-of-the-art ship — equipped with an iron hull and an early steam engine supplementing its sails — Le Lyonnais was built in 1855 for transatlantic passenger and mail service, according to the outlet.

But the French vessel never made it home following its expedition from Le Havre to New York in January 1856 as it collided off Nantucket with the Adriatic, a sailing vessel from Maine on Nov. 2.

The crash left a hole in Le Lyonnais’ hull that caused it to capsize and sink to the ocean floor, The Globe reported.

Major players in the quest to find the wreckage were New Jersey residents Jennifer Sellitti and her partner Joe Mazraani, self-described “lawyers by day and shipwreck hunters on the weekend,” operating Atlantic Wreck Salvage LLC and the vessel D/V Tenacious.

“This one became a passion project for us over the last eight years,” Sellitti said.

Formerly a staff attorney for the Committee for Public Counsel Services in Massachusetts, Sellitti “became obsessed with this ship, and her story,” she told The Globe. “And every little piece of information I uncovered was this sort of this unraveling of what really is an incredible story about this collision.”

Sellitti’s research indicates 114 of 132 passengers and crew members on the doomed ship died.

Among those were Albert Sumner, the brother of abolitionist Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner, along with his wife and daughter; and John Gardiner Gibson, eldest son of Charles and Catherine Gibson, the first residents of Boston’s Gibson House Museum, the Globe reported.

An 1856 report in The New York Times said the collision took place “in a thick fog.”

The Adriatic’s captain, Jonathan Durham, initially expected Le Lyonnais would miss his ship, but after a light on the Adriatic was accidentally snuffed and relit, he saw that Le Lyonnais “had changed her course and was coming directly toward the [Adriatic],” the outlet reported.

The Times report said Le Lyonnais kept going after the collision “and was almost immediately out of sight in the fog.” Durham told the Times his crew “hailed the steamer, and requested them not to leave us, but received no answer.”

Those aboard Le Lyonnais ultimately abandoned ship for lifeboats and a makeshift raft, The Globe recounted.

The Adriatic, which had been bound for Savannah, Georgia, instead went to Gloucester, Massachusetts, for repairs, arriving “in distress” on Nov. 4.

Capt. Durham was later apprehended in France and stood trial for the collision, according to Sellitti, who has written a forthcoming book about the incident called “The Adriatic Affair: A Maritime Hit-and-Run off the Coast of Nantucket.”

To find Le Lyonnais, the team combined what Sellitti had researched with information about anomalies on the ocean floor, which initially came through conversations with fishermen in the area, she told The Globe. Later, the duo used sonar to scan the ocean depths and began exploratory dives of the unknown bumps and masses they were finding.

Assisting in the search was Capt. Eric Takakjian, who had begun looking for Le Lyonnais nearly a decade earlier.

Takakjian said the ship is historically significant.

“Her iron hull construction methods represented some of the earliest examples of that type of hull construction for oceangoing ships known to exist,” he said in a statement.

Last month, their dive crew spent five days in the water examining potential wreckage sites, “and one of those turned out to be it,” Sellitti said.

During Mazraani’s final dive on Aug. 25, he found rigging that confirmed the vessel had sails as well as the engine, Sellitti said.

Sellitti and Mazraani aren’t revealing the ship’s exact location because they plan to continue dives hoping to learn more about the ship’s final hours, according to The Globe.