“Is it Goldstein again?” Richard Nixon demanded.

In July of 1971, the president was infuriated that an unnamed official at the Bureau of Labor Statistics had seemed to downplay the administration’s progress on reducing unemployment while briefing reporters. His suspicions fell on Harold Goldstein, the longtime civil servant and BLS official in charge of the jobs numbers, who had attracted his ire for other comments earlier in the year. Nixon ordered his political counselor, Charles Colson, to investigate. If it had been Goldstein, he said, “he’s got to be fired.”

When three hours elapsed without Colson reporting back, the president called Colson twice within the span of two minutes, insisting that Goldstein had to be guilty. “Give Goldstein, the goddamn kike, a polygraph!” he yelled into the phone.

By the next morning, Nixon’s animus toward Goldstein had hardened into the conviction that the inconvenient numbers from the BLS reflected a problem much larger than one civil servant. He asked his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, to conduct a review. “I want a look at any sensitive areas around where Jews are involved, Bob,” he said. “See, the Jews are all through the government, and we have got to get in those areas. We’ve got to get a man in charge who is not Jewish to control the Jewish. Do you understand?” Haldeman affirmed that he did. “The government is full of Jews,” Nixon continued. “Second, most Jews are disloyal.”

What had started as a fit of pique over jobs numbers was swiftly metastasizing into an extraordinary abuse of presidential power.

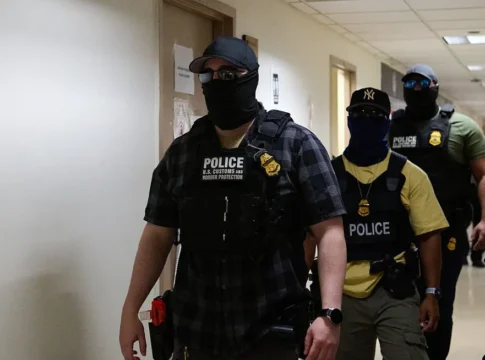

Students and survivors of the Nixon era can be excused for feeling a little déjà vu when they heard the news at the end of last week that President Donald Trump had fired Erika McEntarfer, the BLS commissioner. Trump claimed that the bureau’s latest jobs report was “a scam” that was “RIGGED in order to make the Republicans, and ME, look bad.” As the first federal director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, I quickly thought of the summer of 1971.

For most of its history, the BLS has been as professionally obscure as it has been essential. The bureau’s economists produce the respected and strictly nonpartisan numbers that the White House, Congress, investors, and American workers rely on to know how the enormous and complex U.S. economy is doing—and how likely their next wage increase, job opportunity, or pink slip might be. For presidents to be unhappy with the numbers they get from the BLS is commonplace. But it’s not normal for them to take their disappointment or rage out on the economists who compile them.

In the summer of 1971, Nixon was in the grip of dark conspiratorial thinking. He had been looking forward to positive press from his daughter Tricia’s June White House wedding. Instead, The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers—a classified multivolume compendium of national-security materials pulled together for Lyndon B. Johnson’s secretary of defense Robert McNamara to explain why the United States had gotten into the quagmire of Vietnam. When the former Johnson-era national-security analyst Daniel Ellsberg announced that he was the papers’ leaker, Nixon became convinced that his administration was under assault from smart, well-connected enemies of his Vietnam strategy. So when the BLS official told reporters that a drop in the unemployment rate from 6.2 to 5.6 percent was “a statistical fluke,” Nixon became convinced that Jews within the government were out to sabotage his administration.

Haldeman, although himself an anti-Semite, worried that Nixon’s rage could cause chaos across the government. He decided to try to satisfy the president by focusing only on the BLS. He asked a White House staffer named Frederic Malek to determine how many Jews were in the BLS, and to recommend what to do with them. Knowing that White House documents should not reflect what this investigation was really about, Malek and his assistant used the code word ethnics in their memos as they counted Jews. In February, during Nixon’s earlier bout of rage, Malek had determined that Goldstein had not acted in a partisan manner. But now, instead of questioning his partisan loyalties, Nixon fixated instead on his faith.

The president didn’t get all that he wanted. Although Labor Secretary James Hodgson refused to subject Goldstein to a polygraph test, Nixon didn’t fire Hodgson for his defiance. He also didn’t immediately force out the head of the BLS, Geoffrey Moore, who worked for Hodgson. When Malek found that there were 19 “ethnics” among the 52 top officials working at the BLS, Nixon respected the civil-service protections that shielded most of them, including Goldstein, from dismissal. Instead, he had a supervisor placed above Goldstein and removed some of his responsibilities. Peter Henle, another Jewish economist in the bureau, was transferred out.

After winning reelection in 1972, Nixon required resignations from all of his political appointees. Nixon ignored most of them, but he accepted Moore’s, and the BLS commissioner left a few months shy of the end of his four-year term in 1973. Moore—who wasn’t even Jewish—was the only person to lose his job because of Nixon’s anti-Semitic paranoia.

Nixon’s motives were worse than Trump’s. But in most other respects, the events of the past week provide a vivid illustration of how much more dangerous attempts to abuse presidential authority have become.

Unlike Trump, who lashed out publicly against McEntarfer, Nixon was afraid to own his bad behavior. He did not force out his BLS commissioner in 1971, instead waiting for the chance to accept his resignation two years later. Not wanting his hands to be dirty—as defined by the presidential norms of his era—Nixon constrained himself to abuse power only indirectly. He had no desire to risk public disapproval by firing bureaucrats for specious and explosive reasons.

Moreover, the Haldeman system for running the White House that Nixon first authorized and then tolerated sought to control an impulsive president, not fully empower him. Nixon lacked perfect instruments to carry out his desires; his environment wasn’t greased for enabling. Although he was clear that he wanted to fire a large number of government workers because of their religious background, he proved unwilling or unable to follow through.

Trump exhibits no such constraints. The loyal voters who give him his grip on Congress don’t seem to care what norms he violates. Neither Trump’s Cabinet members nor his White House staff are willing to serve as a check on presidential bad behavior. And so last week, Trump did what not even Nixon had dared, becoming the first president ever to fire his BLS commissioner.

When he is seized by his dark passions, our current president doesn’t even have a Haldeman.