Asala Ferany sat cross-legged inside her tent in a camp near Deir al-Balah, trying to soothe her youngest child. Nada, barely more than a year old, clung to her mother’s neck with tiny, weak arms. The midday heat, nearly 90 degrees Fahrenheit, seeped through the plastic tarp above them. Sweat trickled down Asala’s face, and she had to leave the tent to get some air.

Nada hadn’t eaten since the night before, and the only thing left to feed her was a sachet of peanut paste—one of the last things Asala had managed to bring back from the aid-distribution point that morning.

“This is all I have,” she whispered, tearing a corner of the foil packet and squeezing a bit onto her finger. “I wish I could give her more, but there is nothing left.”

That morning, Asala and her husband, Mohammad Ferwana, had gone for the third or fourth time in a month to an aid center in Deir al-Balah, hoping to get their daughter additional treatment or food.

“The people in the camp look at Nada,” Asala told me. “They say, ‘She is too small. Take care of her. She’s too beloved.’ Some even say she might not survive two more months. I keep hugging her, kissing her. So if I lose her—I’ll know I loved her enough.”

Last month, Asala told me, she took Nada to a government-run health clinic that referred her to a distribution center run by aid groups. There, aid workers encircled Nada’s arm with paper tape, taking a measurement known as the mid-upper arm circumference that’s commonly used to assess malnutrition. As of last Wednesday, Nada’s upper arm measured 4.4 inches—meeting the threshold for severe, acute malnutrition. The aid workers gave Asala 14 red sachets of “ready-to-use therapeutic food” (RUTF), a nutrient-dense, high-calorie paste designed to manage wasting in children.

That wasn’t enough. “I asked if we could have more,” Asala told me. “But they just shook their heads. There are too many children. Too many mothers asking.”

When Asala got back to the tent, she quickly tucked the RUTF beneath her clothes. Her other children tended to eye the packets hungrily, and she needed to make sure that Nada, who needed them most, got her share. All of her children were thin, their ribs visible, but Nada was fading the fastest.

By early afternoon, the camp had gone quiet with hunger. Then, at 1 p.m., a black tuk-tuk rattled down the sandy path between tents.

Word spread fast: The tikkiyya, a community kitchen offered by the World Central Kitchen or sometimes by other volunteers and charitable initiatives, had come. Two dented metal pots sat on the back of the tuk-tuk, filled with hot mujaddara, a simple mix of brown lentils and white rice, stripped of onions or other seasonings that have become unaffordable.

Children rushed from every direction toward the sound. Suhaib, Asala’s eldest at age 9, was already running, a metal pot clanging in his hands. Asala followed close behind. She told me that she accompanied her children to the tikkiya in case their pots tipped or one of them got burned. “It happens. On lentils day, the pots were boiling, and my child was burnt.”

When they got to the front of the line, she pleaded with the aid worker for an extra portion. “They gave two scoops,” she told him. “It’s not enough for seven people.” He looked away, toward the others still waiting for their ladlefuls.

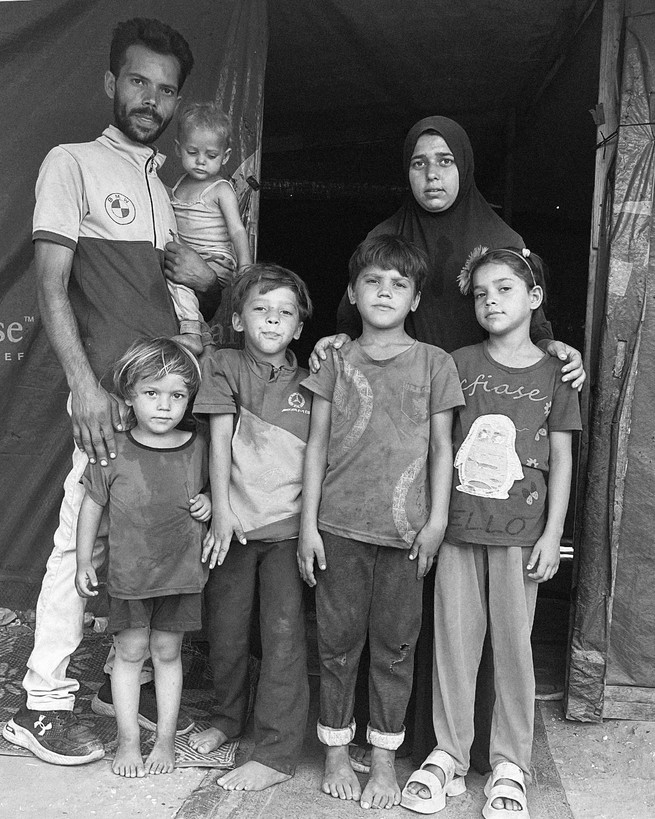

In addition to Suhaib and Nada, Asala has 7-year-old Layan, 4-year-old Yusuf, and 2-and-a-half-year-old Ibrahim. Back at the tent, she gathered them in a tight circle to eat their only meal of the day. “I cannot dare leave one sleeping,” she told me. “Last time, Yusuf napped through the meal. He woke up and found nothing. He cried the rest of the day.”

Inside their tent, once this meal is done, there is no other food at all. Even baby Nada’s milk bottles sit empty, lined up beside other barren utensils. Mohammad, who once worked as a metalsmith in his father’s workshop, now finds himself unable to afford the most basic essentials. In the markets, staples such as eggs, milk, beef, and chicken have all but vanished. For what little remains, the prices are staggering. A kilogram of flour (approximately 2.2 pounds) now costs 120 shekels (approximately $32.50), the same price as a kilogram of tomatoes. Even eggplants—once a modest, accessible item—are selling for 100 shekels (about $27.00) per kilogram.

Nada weighs only 16.5 pounds. She was born under bombardment in May 2024, weighing just 4.5 pounds. “We named her after her grandmother,” Mohammad told me. “Her name means ‘dewdrops’ in Arabic. Something small, pure, and gentle. But nothing about her life has been gentle.”

The family reuses Nada’s diapers, cleaning them with rations of water. With poor nutrition, she easily picks up diseases. “She had fever, flu, diarrhea. I said maybe it’s teething. But she’s not recovering,” Asala told me. “We have no medicine. Even soap has vanished. Doctors said, with these conditions, it is hard to recover, since the immune system is weak and vulnerable.”

The family has been displaced five times—from Wadi As-Salqa, southeast of Deir al-Balah, to a school on Salah al-Din road; then to Mashala, west of Deir al-Balah; to Khan Younis; and now to a makeshift tent in the middle of Deir al-Balah. Their shelter is a patch of plastic and tarp held down by rocks, near the edge of a displacement zone in southwest Deir al-Balah, where Israel was engaged in a military operation from July 20 to 22.

“Shrapnel has come to us,” Asala told me. A child in the next tent was injured. “I worry every day they will order us to leave again,” she said. “Where will we go?”

Asala told me that her children still remember the old days, and the tastes of foods she used to cook. “Fridays used to be family days,” Asala remembers. “My husband brought fish. We cooked chicken. The children remind me of that.” Suhaib used to excel in school. He still asks for a laptop—just to learn on it. Layan talks about university.

In the late evening, Asala’s children again started asking about food. She tried to hush Nada with water, and to distract the others, telling them that the tikkiya might come again tomorrow, or the camp committee might give them something. In past weeks, Asala would sometimes walk to her neighbor’s tents to ask if anyone had a spare loaf of bread. The answer was almost always “no.”

Now and then Mohammad hears about aid trucks passing through the border to supply organizations such as the World Food Program. He joins the crowds of men who follow these trucks, but he often returns empty-handed. At times, Asala has followed him secretly. “I just want to bring something home,” she told me. She described a dangerous scramble, crowds swelling with desperation: “Some bring sticks. Some guns.” Once, her husband returned with a few cans of tomato paste he found on the ground, crushed under people’s feet. “They were cracked open and mixed with sand. I took it anyway.”

The scene around the airdrops can be equally abject. On Wednesday, Suhaib and Yusuf ran toward a descending parachute, yelling: “Throw something here! Throw something here!” Nothing came.

Asala chased it, too. “I left the tent. I wasn’t thinking. I ran barefoot. When I reached where it fell, it was gone. This is what they’ve turned us into,” she said. “I felt humiliated. We are sentenced to live like this.”